My Birth Story is an Expectful series honoring all birth experiences—the beautiful, difficult, empowered, and messy. If you want to share your birth story with us, please fill out this form.

I chose our midwife because she reminded me of a sturdy nun from a children’s book. Her name was Margo and before becoming a midwife, she had been a NICU nurse. She had the “nothing phases me” energy of a life-long caregiver.

I chose her, even though my best friend at the time urged me to go with her midwife, a turban-wearing Kundalini sage, beloved by the LA home-birth community.

Margo would be a steady ship in an unpredictable ocean, and that was what I needed. I didn’t need magic and enlightenment; I needed a rock. An impermeable wall.

My husband teases me that I told him on our first date that I wanted a home birth. (I think it was at least our second.) I was born at home. So was my brother. So were his two kids, my nephews. Home birth was the family way. My parents were hippies—tucked in between the encyclopedias and novels in my childhood basement were flyers for meetups of the radical left and books about yoga from way before yoga was a cultural bellwether. We raised chickens and talked politics while my mom combed the fur from angora rabbits. And we had our babies at home.

I don’t remember anyone objecting or even raising an eyebrow at the choice. If there were concerns from my in-laws or wider friend group, they were kept politely silent. However, my own mother (the hippy) did gently warn me at one point, “Not everyone is capable of having their baby at home.”

Were we closer, I might have taken this chiding differently. As it was, I heard it as a gauntlet hitting the ground: She thinks she can give birth at home and I can’t? Wait’ll I show her.

I went into labor on a Sunday afternoon, on my due date. Contractions started while we were at the Container Store searching for overpriced storage options for our tiny mother-in-law apartment. We went home, giddy, and I started baking—one of my planned early-labor activities. I made a loaf of zucchini bread and a batch of cookie dough to put in the fridge for later. We had heard that the smell of chocolate chip cookies in the oven stimulates oxytocin. (These are the kinds of tips you get when you’re having a home birth.)

We tried to sleep that night but woke every ten minutes to log my contractions instead. In the morning we called Margo. She listened politely and then told us we should call her again when the contractions were closer together.

From the moment those blue lines show up on the pregnancy test women are ushered into a world of plans and presumptions. Will it be a boy or a girl? Will you breastfeed or formula feed? Will you go back to work or stay home?

But no question is more pressing than, how will you give birth? Friends tell us horror stories or heroes’ journeys. Strangers on the street reach for our bellies and make predictions. Before you have a child, birth is everything. There is only one tangible incontrovertible truth of pregnancy: this baby is in my body and one day it will exit. We think that how the exit happens marks us as mothers, and them as children, forever.

I knew women who told humble stories of their pain-free births. Lithe yoga goddess women who didn’t even know they were in labor until they were ten centimeters dilated. They were avatars for the perfect birth. Effortless, earthy. That was the woman to aspire to: the one who could walk through every contraction singing, a tribe of other women following in her path.

I was head-in-bucket mid-vomit when Margo and Kelly, her assistant, finally arrived late Monday night. They took one look at me and hustled me off to the bedroom to check my progress. Upon examining me they said a non-committal, “You’re making progress,” but offered no specifics.

I would later find out that at that first check, nearly thirty hours into labor, I was zero centimeters dilated.

Zero.

We were sent on a walk. Every few steps I had to grab my husband and sway through a rollicking contraction. As I clung to him, I remembered a quote from another woman’s birth story about how comforting it was to hold her husband’s unchanging body during labor, as hers seemed to be nothing but change. Looking back, I have to wonder if the earthquake of labor is purposefully disorienting: get ready, your body is saying, nothing will be the same from here on out.

The night dragged on.

At some point, we set up a kiddie pool in case I wanted to labor in water. I circled it like a blue whale, groaning into the wet. My husband tried to put the cookies in the oven, but I forbid it. Nothing sounded worse to me—nothing—than the smell of chocolate chip cookies.

By the next morning, Tuesday, I was finally showing a little progress: six centimeters. I wept on our bed, my head in Margo’s lap.

“I can’t do this,” I told her.

“You are doing this.” She said, rubbing my back with her warm wide hands.

If everything progressed as it should, she told me, I would continue to dilate about one centimeter per hour. Could I try for four more hours? It felt insane. Impossible. But I nodded, yes, I could try.

I got back in the tub and the three of them—the two midwives and my husband—murmured to me like sideline coaches pumping up a boxer. I shouldn’t cry out when the contractions came. I needed to moan quietly, from deep within, so as not to rattle my own nervous system. They taught me to blow out in steady bubbles as the contractions rose and fell.

I became a labor ninja, diving under the pain and emerging again, over and over. Victorious. After four hours they pulled me from the tub.

My cervix hadn’t budged.

What I didn’t know then was that I was being given early access to one of the great truisms of parenthood: I was not in control. Never had been. Any illusions about playlists or right positions or oxytocin-inducing smells were just nice stories told to make the unknown seem knowable.

So at 5pm on Tuesday, fifty-three hours after labor began, my husband loaded me into our car— the one we had driven into the mountains for our wedding just a year and a half earlier, the one that now held our brand-new infant car seat—and drove us the endless bumpy drive to the hospital.

I would have named our child after the hospital anesthesiologist if I could have, so great was the relief of the epidural he administered. For the first time in two days, I was able to take in my little team—my husband, who had held me, squeezed me, stayed with me every minute until I finally begged him to sleep for his own sake—and my midwives, steady and tireless. I slept under their watchful gaze.

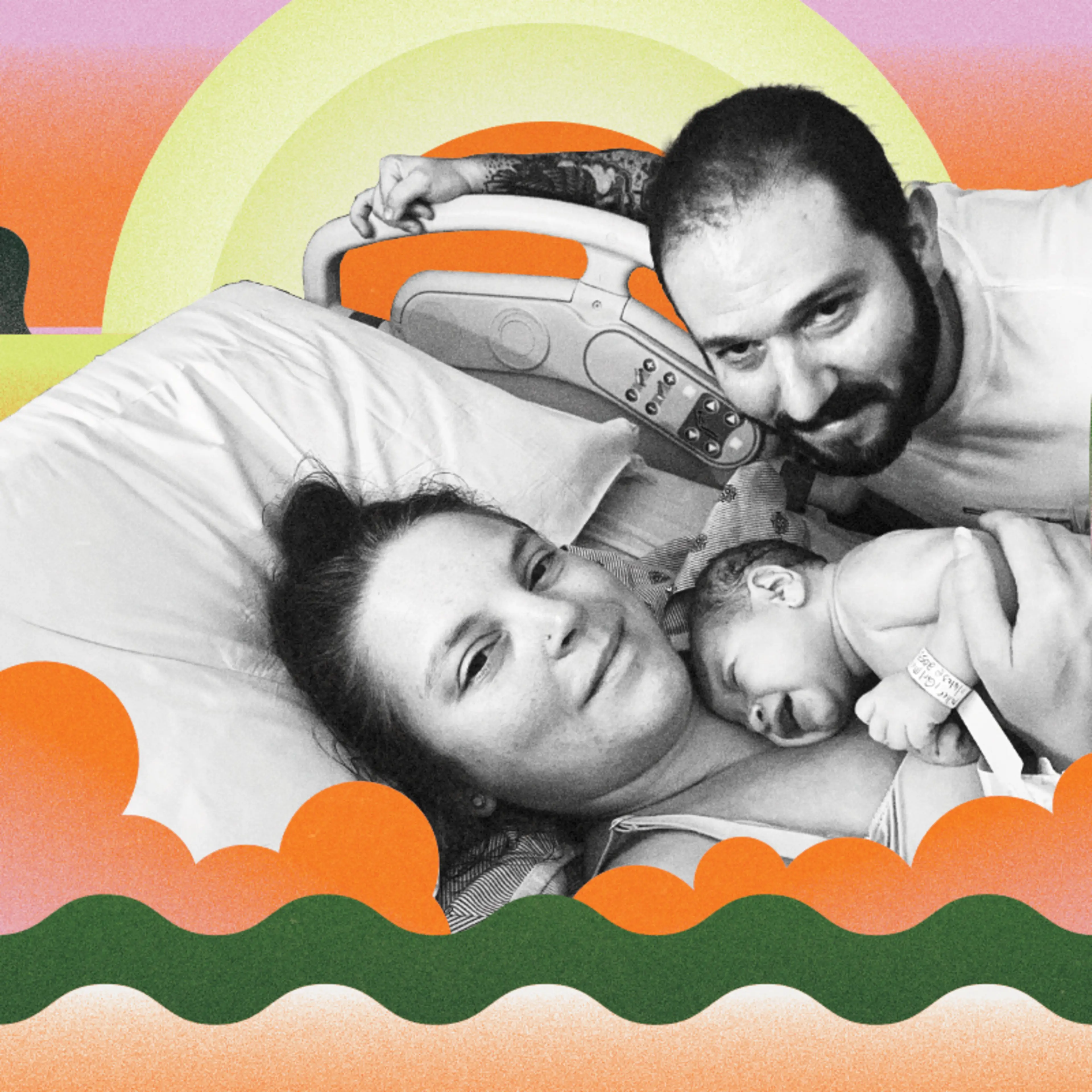

And then, what had been Sisyphean—all uphill struggle—became an effortless glide. Like finally pointing a wave-wrecked boat downstream. My water broke. I dilated the remaining four centimeters, and my daughter was born: enormous (9 lbs 10 ozs), sunny-side up (which explained the extreme pain and lack of progress), and utterly, gloriously, perfect.

In the aftermath of her birth, I wondered if I ought to feel like a failure. I saw other people watching me for signs of self-recrimination, but it never came. If anything, my only regret was that we didn’t go to the hospital sooner. Why had I been so stubborn? What had I been trying to prove?

Becoming a parent is terrifying, and birth is the entry point. We think if we can control that, maybe we can control all the rest of it, too. Like a baby birthed without medication will translate into a happy child and teenager and grown-up who won’t have to suffer the winds of constant change. Or won’t have to suffer, period. But parenthood is unpredictable. Life is unpredictable. You can grip down in those moments and spend forty hours willing yourself toward what you want, or you can climb out of the pool and drive towards destiny.

Births that go perfectly according to plan aren’t gifts handed out to the worthiest. Just like when your child is agreeable or talented or empathetic—that’s as much luck of the draw as when they hurl themselves to the ground in the grocery store because you asked them if they wanted the strawberry yogurt instead of the blueberry.

To parent well is to flex when the road curves. Because it will. It will hurl you right off the tracks. But if you can bend and shift and adapt, you will find yourself right where you need to be. Looking down at your child—exhausted, hungry, blown open in the best way—and so grateful for the road you took to get there.